I am not Neil Bhat

A reflective essay on an MFA graduation show

by Neil Bhat

In my graduation show Thank God I am not Neil Bhat, both identity and position were continuously destabilized: deconstructing narrative around the subject with an installation that rejects all positions within it, and artworks that collapse like sandcastles at closer inspection. An orchestrated collapse of meaning that preconditions new meaning, and a grammar of the unknowable that generates more than it is fed with.

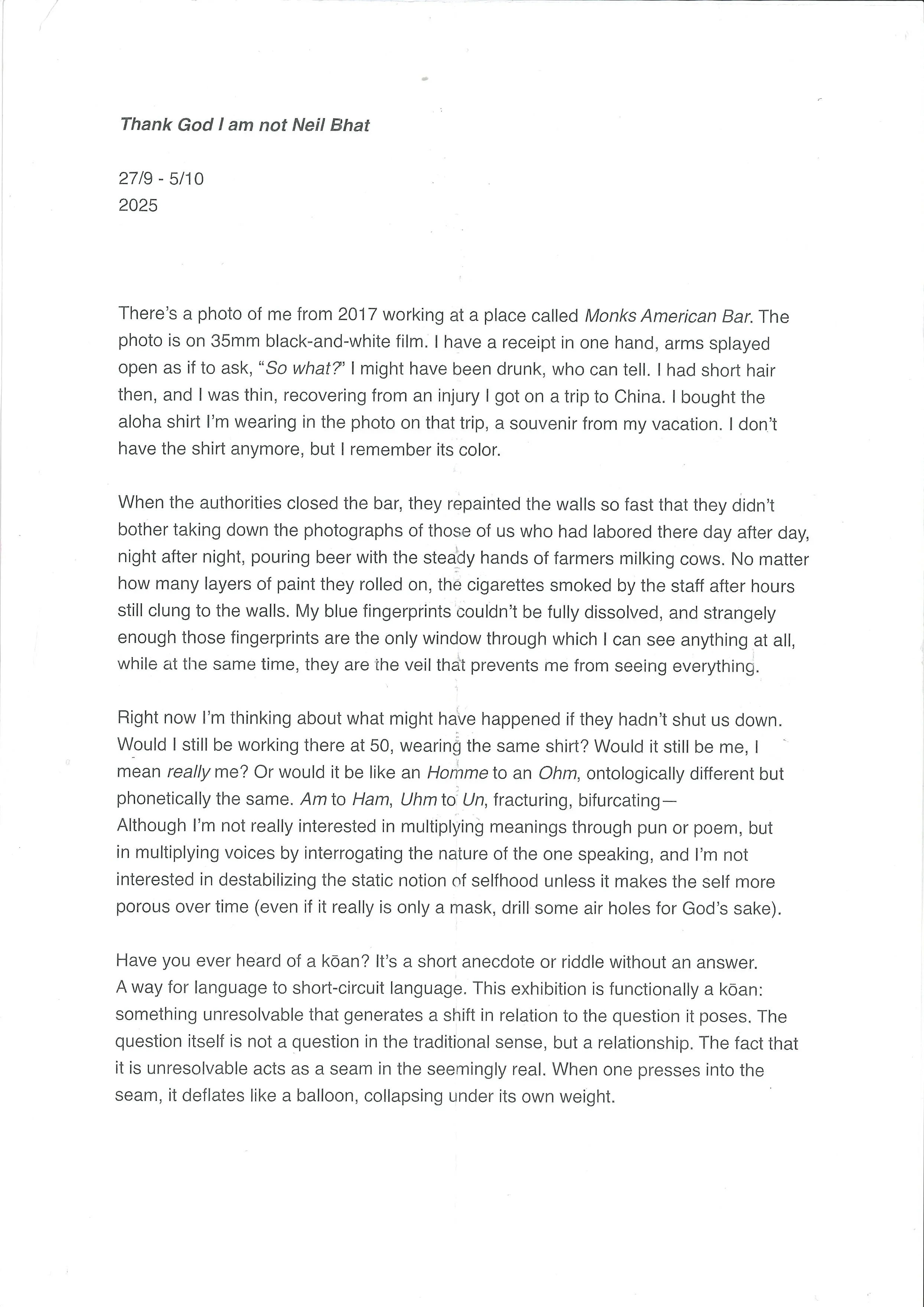

On September twenty-sixth, 2025, my solo presentation Thank God I am not Neil Bhat for the MFA program at the Royal Institute of Art opened at Galleri Mejan.

Over the course of nine days there were four hundred and sixty visitors to my and my co-exhibitor Ebba Birkflo’s exhibitions (not including the myriad of students, staff, socialites, art-world aficionados, collectors, curators, and vernissage wine grifters who came to the opening). Having been present in the room on most days, I believe I can confidently sum up the visitors’ reactions in two categories: “!!” and “??”.

This essay is aimed at the latter of the two, to give access to the inner workings of an exhibition that could not be clarified—an exhibition that would fail the moment it became legible as an answer.

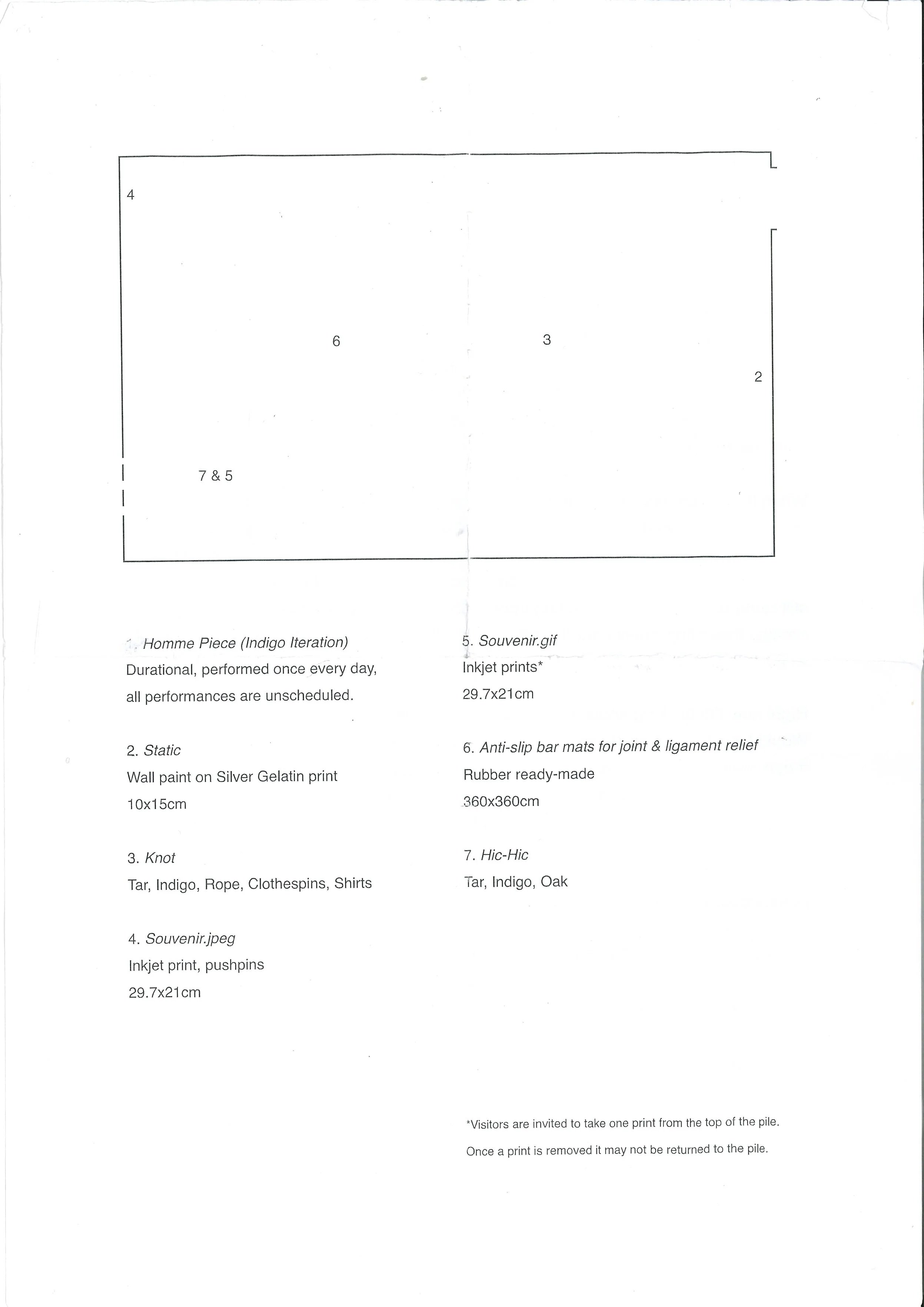

Neil Bhat, Thank God I am not Neil Bhat, 2025 Installation view, Galleri Mejan Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger/Royal Institute of Art

A series of closed doors, right to the face

One visitor theorized that this divide (“!!” & “??”) had to do with frequency; if you were tuned into the wrong station you couldn’t hear anything, just static. The refusal to articulate, to open the door when someone comes knocking, could be taken as a refusal to grant access. But the refusal to articulate is also the refusal to grant the safety of an explanation—a safety that would have been unpedagogical and counter to the stakes of the exhibition. Rather than the presentation of a concept, Galleri Mejan was transformed into a place where you experience a concept: a resonance chamber whose function was to amplify what you bring with you.

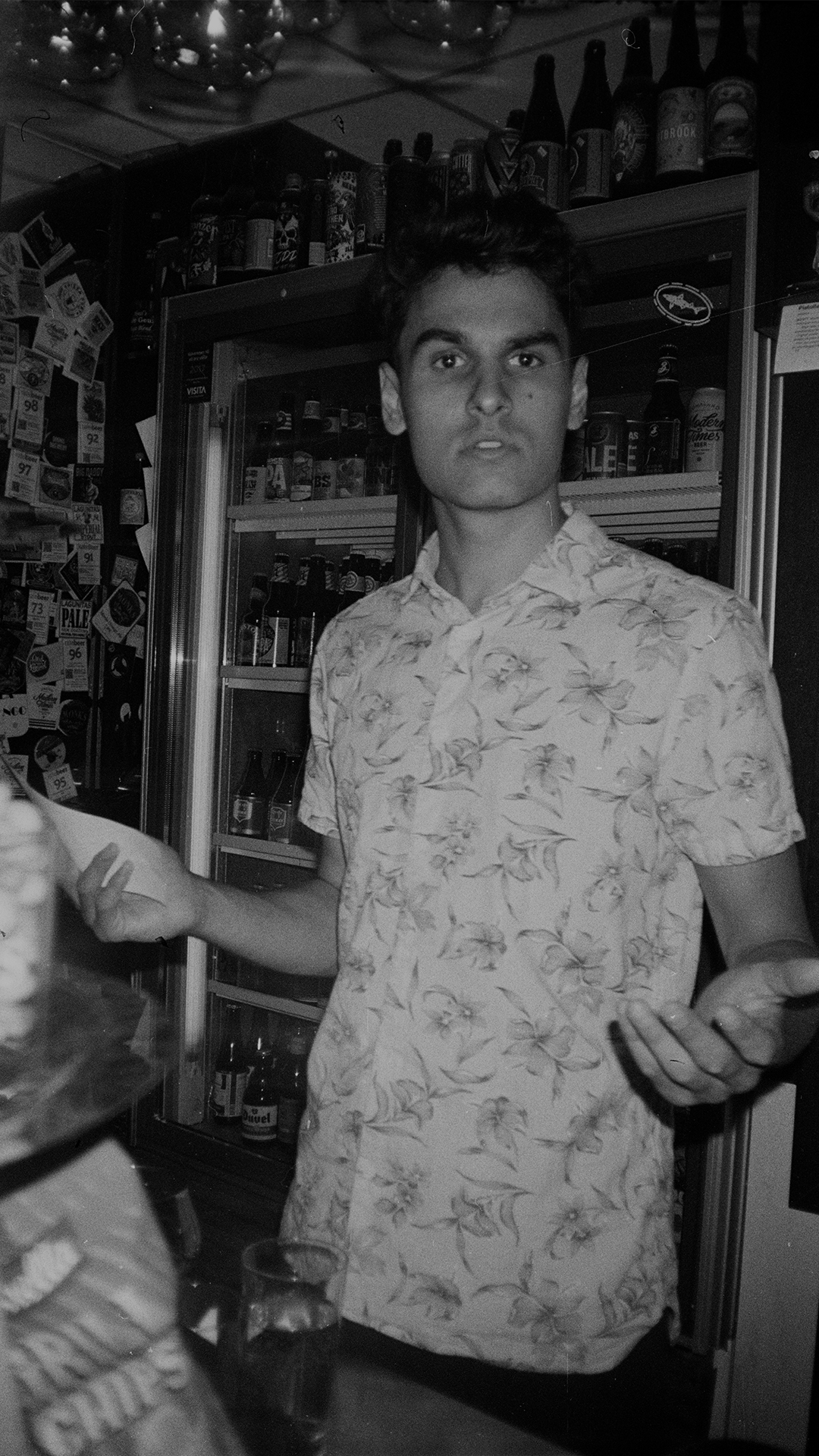

For you, it actually all started weeks before entering the room. The sole purpose of the invitational image (traversing social media, email, and the Royal Institute’s website) was to imprint itself on your retinas, the set-up for the punchline on the 26th of September. It was a grainy black-and-white image of me working behind the counter at Monks American Bar in 2017: a faraway look in my eyes, a receipt in my hand, and an aloha shirt on my shoulders. For me, the image was a memento, a memory, and a fear all packed into one—the fear of succumbing to a night job, the metaphysical anxiety of another self haunting me from the future. For you, it was the beginning of an expectation that would never be met: this particular image of me would never be physically present in the room.

Neil Bhat, Thank God I am not Neil Bhat, 2025 Installation view, Galleri Mejan Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger/Royal Institute of Art

Allow me to describe to you the room, and perhaps how you as a visitor may have navigated it:

When you enter, after ignoring the stack of press releases, you are met with a white void and a clothesline cutting the room in half, a rubber mat acting as a de facto stage. At the far end of the wall you see what you think to be a print of the image on the invitation, but as you brush past the aloha shirts hanging from the clothesline and draw closer, you notice that the face is distorted, aged—a simulacrum, someone other than the 23-year-old Neil Bhat you saw on the invitational image.

You notice the spent objects strewn across the bar mat—clearly, you have missed a performance: stained rubber gloves, a silver cocktail shaker, and brass gunghroo (Indian ankle bells). There is a carved wooden stool next to the mat with a stack of images, the same as the one pinned to the wall. You take one from the stack, fold it up, and put it in your pocket, unaware that each image in the stack is marginally younger than the one above, the difference not apparent at first. You don’t know that in two days of visitors taking sheets of paper, I will be visibly younger than the image pinned to the wall. Maybe you forget the sheet folded in your pocket, and in two weeks’ time the material will have degraded while the image printed on it stays the same.

Neil Bhat, Thank God I am not Neil Bhat, 2025 Installation view, Galleri Mejan Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger/Royal Institute of Art

You look back the way you came, peering through the aloha shirts, and notice another image stuck to the wall—the shadow of the invitational image—rolled over with wall paint, protected only where the push pins hid the silver gelatin from the roller. Like an optical illusion, the closer you get to the surface, the more it dissolves into static.

You turn, and the aloha shirts taunt you. There is a gap—one is missing, the one used during the performance of the day. You look at your phone and try to discern from the patterning of the black-and-white image which shirt is the one in the photo. It isn’t there.

Neil Bhat, Thank God I am not Neil Bhat, 2025 Installation view, Galleri Mejan Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger/Royal Institute of Art

Empty shirts superimposed over an empty stage—what are you looking at? What are you missing? Seeing the performance will probably give it away. You go back to that stack of press releases and read: All performances are unscheduled.

A teacher at school suggested that there are two ways to approach installation art: one is through the dramatic, borrowing operatic spectacle to pump up the volume of a viewer’s experience; the other, more “pure” installation has to do with making every position one can occupy in the space the obvious place to be—there is no wrong place, it’s all just a feeling of correct relationality. My room had no right place. It rejected you no matter where you stood. It was subtle, but everything pushed you from one position to another in a whirlpool of “not quite right.”

Empty image, empty shirts, empty stage, empty schedule—every single work is an empty cup, a closed door, stepping stones that lead to a locked gate. Even the press release is shut tight. It had to be, because the moment it could be effectively used to prop up the collapsing works, the show loses its teeth. It performs collapse, and any grammar relating to unknowability generated from the smoke becomes hypothetical. What kind of viewer would be produced by providing an answer to the unanswerable? The paradox, the mystery, degraded to hypocrisy.

On the topic of locked gates: a key concept in Zen practices is that you can’t unthink your mind; you have to relax your body. But at this point in the exhibition you might try to force your way through the door. Like a finger trap, the door doesn’t respond to force. You project onto it—this is a show about identity! There are cultural artifacts, objects of labour, and an individual’s name branding it. You leave frustrated, with an answer like an ill-fitting shoe—or barefoot, excluded from the secret you think I’m sitting on. The frustration is normal, but what can you do when met with these closed doors? You can wait, and if you’re lucky, you will realize the doors weren’t hiding an answer from you after all.

How many people, stressed out from their daily grind, actually slowed down and breathed when met with frustration? At what point am I asking too much? At what point is every gesture just too small?

Neil Bhat, Thank God I am not Neil Bhat, 2025 Installation view, Galleri Mejan Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger/Royal Institute of Art

The grandest gestures possible without becoming totally imperceptible

While I was working on which gestures to hone in on, I was thinking about scale and volume (how small, and how quiet). Transforming Galleri Mejan into a resonance chamber required surgical precision, a razor that cuts when held too tightly.

The most illustrative examples of this methodology were Souvenir.jpeg (2025) and Souvenir.gif (2025). Understanding how much effort went into this off-the-cuff, mass-printed appearance is an important part of understanding the teetering balance the room was in.

The A4 format is invisible; it implies its own mass production and portability. It is the aesthetic of the press release, the exhibition map, the list of prices. Usually, the only thing one leaves an exhibition with is a folded-up A4 sheet in the pocket. I wanted the A4 to be the stage for my simulacra, but I didn’t want the white margins of the sheet to act as a frame for a photograph. I wanted the image to fit perfectly in the corner without borders.

Of course, a printer can’t print zero margin, because the teeth in the machinery need something to hold on to—I had to print on A3 and then manually cut the image down to A4. This, in addition to specifying the exact degree of fuzzy pixelation in order to hide the AI alteration while still being legible; the tone of the image (black-and-white images printed in color settings have a vastly different temperature and resolution than images printed in grayscale directly from the printer); creating a smooth shift from image to image for the GIF so that the difference is imperceptible between layers but visible over time—the manic fixation on the microscopic, the edge of a razor perfectly honed so that when you touch it, it cuts you, whether you see it or not.

In Knot (2025), the removal of a different shirt each day changes the entire room—the color palette shifts, the vantage point on the stage changes. One classmate said that she visited the show maybe twenty times, more than anyone: to see my performances, my examination, to document, to photograph. She told me that she realized the room was a totally different room each day. Even a cloudy sky changed the mood in the naturally lit space. A few other people revisited the show, and they felt the room shift beneath their feet—projecting what they had in their own psyches that day onto the row of shirts and empty stage.

But it isn’t just the room that is different from one day to the next. I am proposing that the difference between self from one day to the next is imperceptible yet ontological. Different versions of an aloha shirt, different variations in the same performance, different sheets of paper bearing an image with an unnoticeable difference from the previous. But the difference is there whether you notice it or not. There are just some things that cannot be mastered by a viewer, no matter how trained, intelligent, or sensitive (or even how many times they return to the room). Some differences are structurally ungraspable, no matter how large your microscope. It is when the viewer accepts that fact (no easy feat) that the show begins to breathe.

Neil Bhat, Thank God I am not Neil Bhat, 2025 Installation view, Galleri Mejan Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger/Royal Institute of Art

Hom(me)ophone

The performance Homme piece (Indigo iteration, 2025) is, on paper, quite a straightforward action. I’ll try not to complicate it too much.

I enter the room from backstage wearing one of the nine aloha shirts from the installation Knot (2025), circle the installation Anti-slip bar mats for joint and ligament relief (2025) counterclockwise several times to find the day’s rhythm and tempo, take off one shoe (either left or right) at the edge of the mat, and then enter the stage. Once on the stage, I tie the brass gunghroo to the ankle without the shoe, and then choose to work with either the rubber gloves (one hand clapping) or the cocktail shaker (the urn). If I have chosen the rubber gloves, one of the sounds I will use in the performance will be clapping—sticky rubber against sticky rubber. If I have chosen the cocktail shaker, I will tap the silver lid against the body of the shaker. I do not know which object I will work with until the moment I pick it up.

The sounds produced with either object are combined with a shaking of the bells and stomping of the feet, impact reduced by Anti-slip bar mats for joint and ligament relief (2025). The moment I fall into a predictable rhythm of movement or sound, I immediately change intensity, tonality, pacing, movement, or placement. The vocal component is the repetition of a single word: “Am.”

The room was so devoid of sound absorbers that it acted as a literal resonance chamber (as opposed to a metaphorical one), amplifying every sound I made—from words, to the creaking of bones, to breath growing ragged. “Am” is repeated over and over with various tonalities and intensities, tuning and retuning to my body and mood. As the word is repeated, homophones emerge: Homme, Ham, I’m, Uhm, Ohm, Om, and so on. But it isn’t the meaning that is different from one “Am” to the next. I am proposing that the difference between self from one moment to the next is imperceptible yet ontological. Infinite versions of you are watching infinite versions of me, split far more times than the tenth of a second it takes to utter “Am.”

Once I have tuned into myself, I take off the gloves or drop the shaker, remove the gunghroo, put on my shoe, and leave the space, breathing rhythmically to the new momentary self-attunement.

Neil Bhat, Thank God I am not Neil Bhat, 2025 Installation view, Galleri Mejan Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger/Royal Institute of Art

My identity is a uniform for a position that doesn’t exist yet

The show is not about my identity, secret codes, or traumas that come with being a third-culture kid. In this room, the self is acting as a uniform that the show wears while it does its work. The deliberate staging of self could easily steal the spotlight (and at a glance, it does), but identity here is a departure point—don’t get stuck staring at the finger pointing at the moon. The uniform is convincing. As you try to recall the show’s face, it blurs, hidden behind the nametag. Everything bears the traces left by my hands, the sweat of my back, and blood from my ankle.

But what you are looking at is not an individual having difficulty pinpointing their identity; it is the display of an individual caught in between becoming and unbecoming, dissolution and stasis, unraveling but still being made of yarn. When one mask comes off, another is there to take its place. The consistent misreading of the exhibition as one about identity is not incidental but diagnostic. The viewer’s desire to stabilize the bothered subject invariably causes fixation upon the subject. Perhaps the viewer feels discomfort from the unstable ground and seeks stability wherever they can find it.

So why Neil Bhat? Why stage my identity in this way when a fully fictional character could have served (perhaps) equally well? But aren’t the stakes much higher when it’s a “real” identity we are dealing with? Everyone knows Frosty the Snowman is fictional; to claim that I am fictional is much more challenging, but also potentially more generative. To watch the showman Neil Bhat melting like a snowman in the spring, the water from his body feeding the grass before evaporating in a room full of sunshine and aloha shirts.

To be clear: this show was never about identity. It was always about perspective and the deconstruction of self (I am transient, I am an unfixed wave), and I am not intent on displaying any trauma beyond what eeks from my fingertips (I am static, a fixed point on the trajectory of my past), and so I don’t address it. Instead, an invitation is extended to linger in the impossible question, the paradox, which invariably leads to a profound shift in the relationship one has to oneself. It is here that the notion of the inert self is bothered. This exhibition never contained or withheld truth. It withheld resolution. Resolution would have reinstalled the stable sense of self it works actively to unsettle, and so the doors had to stay closed.

The essay I am not Neil Bhat (2026) was first posted on the 29th of January 2026